Up next on our linguistic tour du monde, we head to the East African Community (EAC) with its lingua franca of choice, Swahili. The Bantu languages stretch far and wide from the southern tip of the continent up as far north as Cameroon.

The basics

The Bantu languages are an incredibly diverse and historically rich family with trade, cultural exchange, and migration almost built into the languages’ fabric. This article will focus on Swahili, as it is the language with the most speakers in the family (estimates range from 70 to 200 million speakers), as well as the language with the best availability of academic resources.

Swahili is primarily spoken as a non-native lingua franca, a language spoken between people with no common native language (a role English fills in Europe and Southeast Asia, for example). With only an estimated 5.3 million native speakers, centuries of commerce along the Swahili Coast carried the language far inland throughout eastern Africa, and modern diplomacy and economic cooperation have only continued that tradition.

Why is this language interesting?

I find Swahili fascinating because it strongly represents the assertion of African culture and identity in the face of an increasingly globalised world. Diplomacy between most nations outside of the EAC is handled almost exclusively in English or French, echoes of the continent’s colonial history. However, Swahili never truly lost its foothold as the language of education, culture, and trade south of the Horn, and has re-established itself strongly (with the constant lobbying of Kenya and Tanzania, where most native Swahili speakers live) as the primary language of affairs across almost a quarter of a continent.

Swahili is a deeply overlooked language on the global stage, with most outsiders not even sparing a thought for potential linguæ francæ outside of the European global norm; English, French, and Spanish dominate the global perception of what it means to be an “international language”, while languages like Swahili fill the many regional gaps that they leave behind.

Writing systems

Swahili was first written in an unmodified Arabic script, borrowed from its trading partners on the Arabian Peninsula. This script evolved over time in several regional directions without much in the way of standardisation, with attempts at reform and unification largely unsuccessful throughout the 19th and 20th century. These evolved forms became collectively known as Swahili Ajami, of which author Chapane Mutiua has written an in-depth overview.

Today, Swahili is written almost exclusively in the Latin script, introduced by Christian missionaries during the colonial period. This reflects a much broader trend: Swahili is one of countless languages to have its existing writing system displaced when Europeans came knocking; from Vietnamese to Inuktitut, spreading “the good word” reshaped entire languages and cultures across the world.

Ancient trade to modern diplomacy

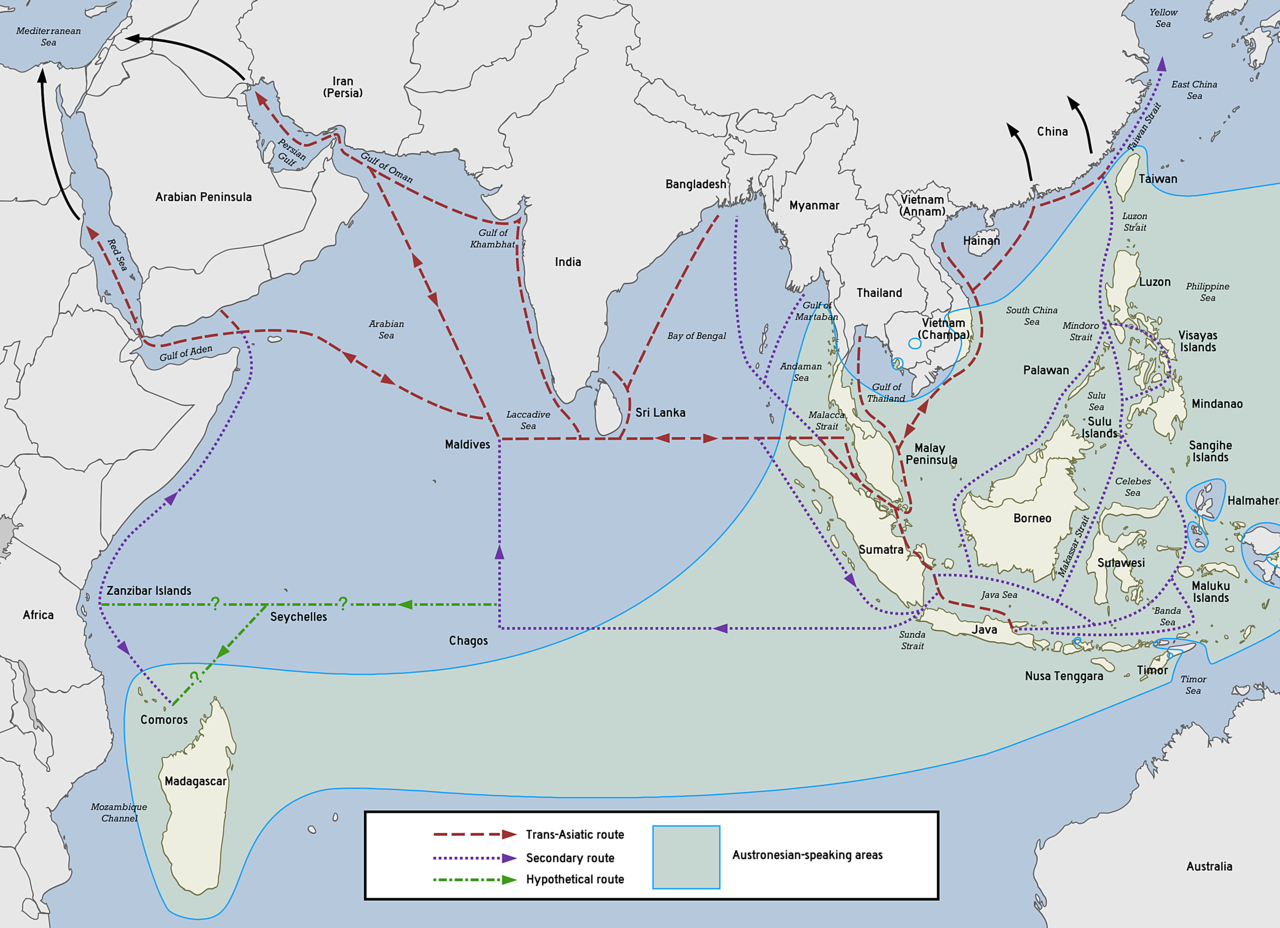

Swahili and its predecessors have been the language of trade in East Africa for essentially all of written history. The language has absorbed vast quantities of vocabulary from Arabic, Persian, and more recently Portuguese and English. Even the name “Swahili” comes from Arabic سَوَاحِل (sawāḥil), meaning coasts. The language was internationalised before that term even existed.

As stated previously, Swahili is one of the three official languages of the EAC (the others being English and French), but the language also has official status in 4 countries: Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. Uganda is notable as Swahili people make up less than 1% of its population, but the language is nonetheless one of its only two official languages. Rwanda also lacks almost any native Swahili population, but the language is one of four official; the status of the language serves to mark political belonging and integration more than direct utility to its own population.

Using Swahili at political summits and trade talks is a political statement for decolonisation and Africa-first policy. The language has become a sort of “neutral ground”, allowing discussion out from under the looming historical weight of a European lingua franca and without the bureaucratic headache of organising interpreters. The language having such a small native speaker-base also helps with this, as using Swahili can avoid seeming to favour one ethnic group over another in the intensely multicultural countries of East Africa.

The language of Africa?

Swahili’s East African reputation of neutrality has seen it championed as a potential Pan-African language since the 1960s. An estimated 13% of the continent already speak the language to some level, so wider adoption, it is argued, would be the most practical way to establish a collective African identity and culture. This goal has been most prominently realised in Tanzania, where despite having over 100 native languages, Swahili is now also spoken by over 90% of the population due to its use in government, media, and education. The former colonial language of English is only spoken by 10% of the population, in comparison.

The African Union adopted Swahili as its sixth working language in 2022, the first native African language to be used in this role. This follows other moves to adopt the language, with it now being taught in Ethiopia, Botswana, and South Africa, it seeing adoption as a working language by the Southern African Development Community, and it increasing in cultural influence across the continent.

It would, however, be premature to outright conclude that Swahili is becoming the pan-African language that post-colonial idealists have long envisioned. Swahili faces stiff competition from the European languages of Africa’s past, with France in particular maintaining a kingmaker-like diplomatic presence in West Africa. Much of that influence remains due to France’s chokehold on monetary policy in much of Africa through control of the CFA francs, a mechanism that grants Paris immense political leverage and keeps the Sahel largely dependent on it to this day.

The language also faces competition from Arabic in the north, with the Arab League’s political influence and relative stability long encouraging even non-Arabic-speaking nations to adopt the language for trade, governance, and culture. Arabic and French, however, lack the political neutrality afforded to Swahili; each carries the baggage of invasion, conquest, and colonialism throughout Africa.

Conclusion

Swahili has been heavily overlooked by the international community, but the language is quickly gaining traction due to a decades-long political campaign stretching across the continent. Its use in culture, media, and diplomacy only looks set to increase in the coming decades as Africa continues to redefine herself after a century of colonialism and repression. The language faces hurdles and competition, but the future looks red, black, and green.

Leave a Reply